Quetta Diaries | A Journey Through Balochistan’s Quiet Majesty

Nestled amidst rugged mountains and kissed by cool winds, Quetta—Balochistan’s capital—isn’t the kind of city that clamors for your attention. Instead, it pulls you in gently, offering glimpses of a way of life that feels both distant and deeply grounding. My recent visit to Quetta, along with nearby escapes to Ziarat and Hanna Lake, offered a much-needed reminder of how profoundly beautiful cultural preservation can be—and how, sometimes, systemic barriers can mar that experience.

The Culture That Greets You

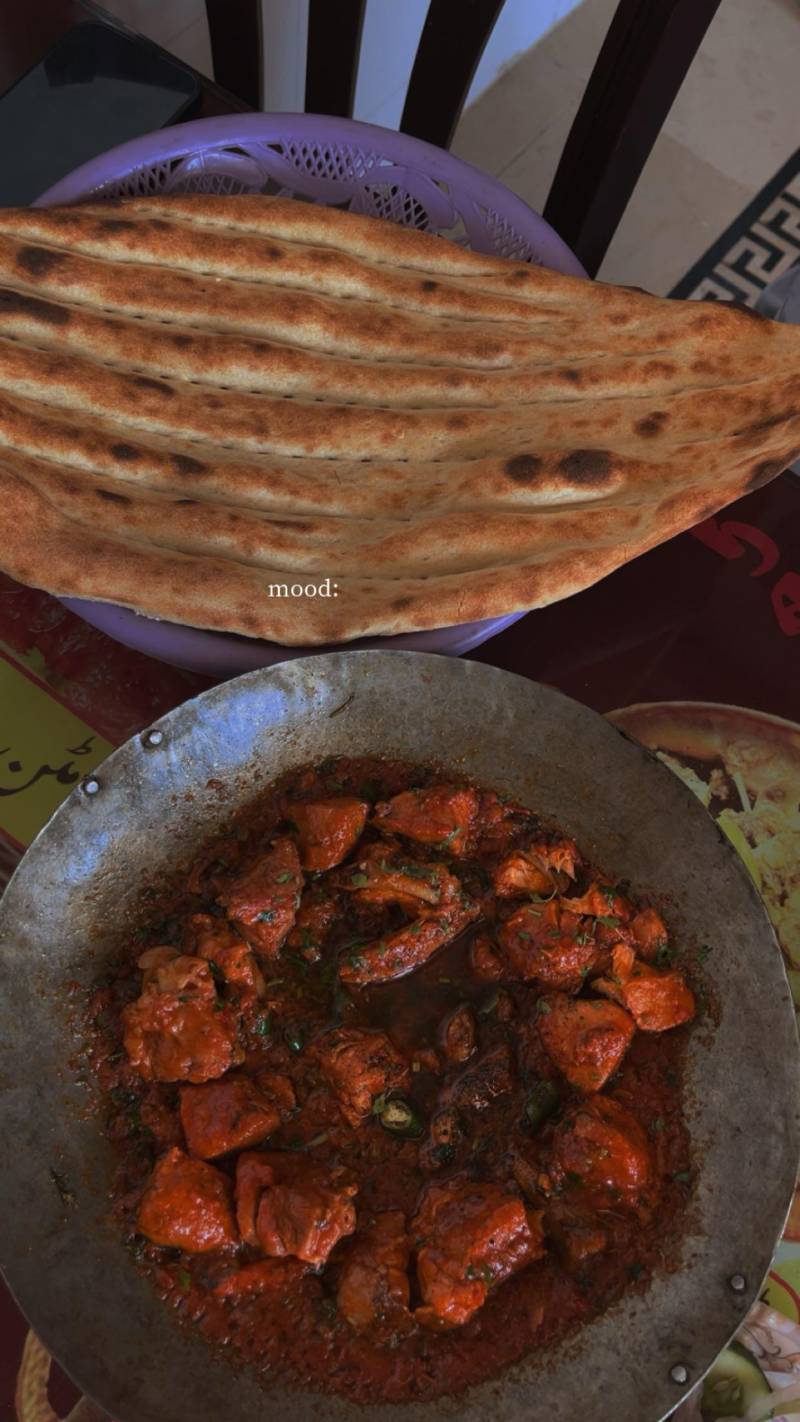

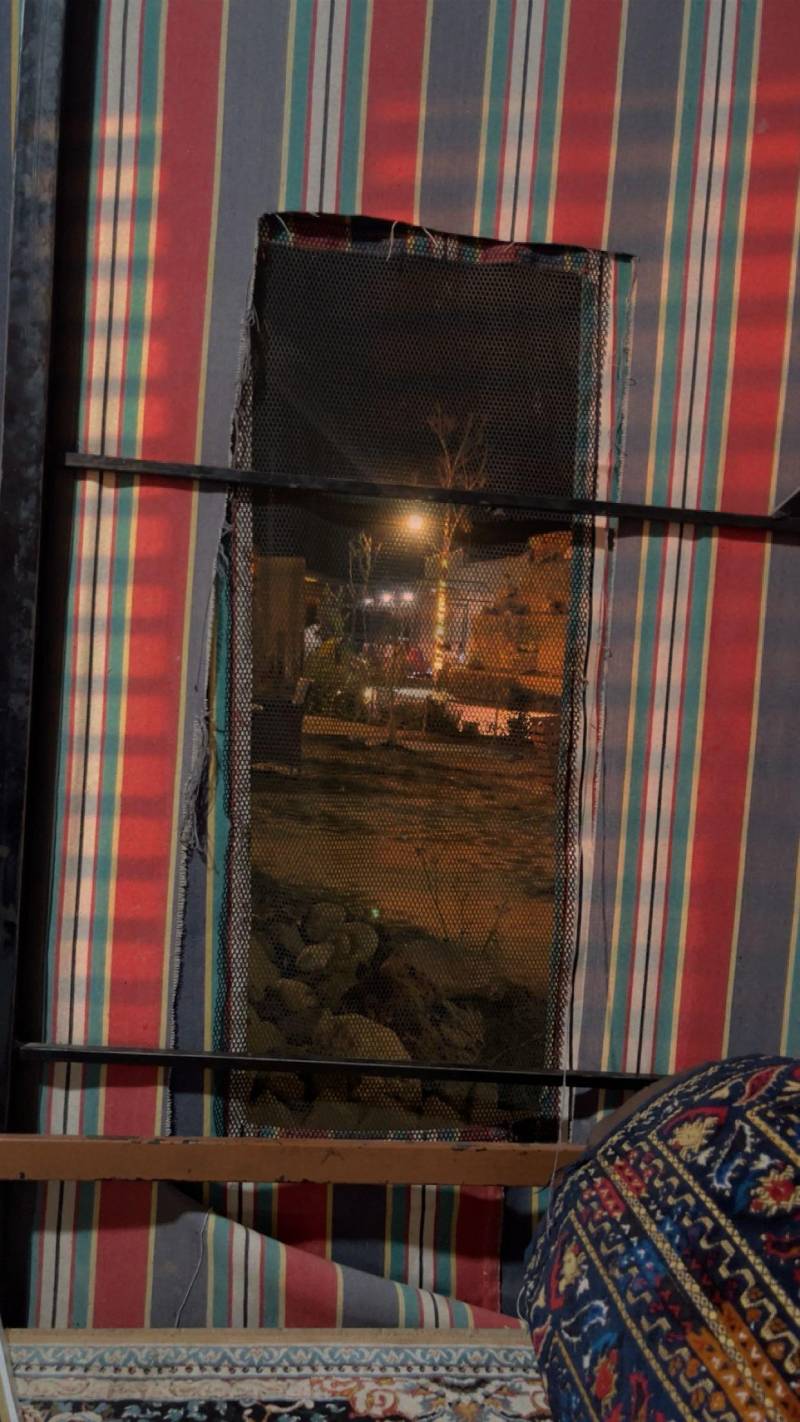

Quetta is conservative, yes—but not in the rigid, reductive way outsiders often assume. Its conservatism carries a warmth and dignity that’s hard to articulate. It’s in the quiet respect with which traditions are upheld. Every restaurant I visited had a separate family hall—not a commercial gimmick, but a sign of a culture that values privacy and hospitality. Outdoor eateries, meanwhile, often feature traditional Balochi seating: carpeted floors, round pillows, and low tables under open-air tents. Sitting cross-legged with food shared from a central platter, you don't just eat—you experience.

This sense of tradition continues in the way the city carries itself. The mountains that ring Quetta aren’t lush or green in the typical sense. They’re rugged and stoic—majestic in a way that feels ancient. Composed largely of sedimentary rock, they rise like sentinels, reminding you that you're in a place shaped by centuries of resilience.

Ziarat and Hanna Lake: Escapes That Stay With You

Just a few hours from Quetta lies Ziarat, a hill station famed for its Juniper forest—one of the oldest in the world. The drive alone, with winding roads hugging the mountains, is enough to quiet the mind.

At Ziarat Residency, where Pakistan’s founding father Muhammad Ali Jinnah spent his final days, time seems to slow down. There’s a haunting stillness to the place, a reverence that makes you reflect.

Hanna Lake, in contrast, brings color and light. Surrounded by rocky cliffs, the lake gleams like a sapphire set in stone. Families gather here, children paddle boats, and conversations flow over cups of tea. It’s one of those rare places where nature and nostalgia meet.

A Tale of Two Cities: Beauty and Barriers

But even as Quetta captivates, it frustrates.

One of the more jarring experiences was attempting to visit areas within the cantonment zone. Unlike other cities in Pakistan where cantonments are part of the public landscape, Quetta’s is nearly impenetrable. Even with valid ID, you’re often denied access unless you hold a separate ‘cantonment pass’—a document that functions more like a visa than a local permit. Visitors are frequently stopped, interrogated, and made to feel like they’re crossing an international border. Residents I spoke to expressed exhaustion and dismay—many simply avoid the area altogether, despite having friends or family inside.

While security concerns are understandable in a region that has witnessed its share of turbulence, the level of restriction in some areas felt excessive. It reinforces an invisible divide: between those who belong, and those who are made to feel like outsiders in their own homeland.

The Promise of Progress

Despite these concerns, Quetta is evolving. New infrastructure projects, expanded roads, and investment in public spaces are signs of progress. Yet the city retains its soul—a rare feat in a world where urban development often steamrolls over culture.

Perhaps that’s what struck me the most: Quetta doesn’t try to reinvent itself. It doesn’t pander or perform. It simply exists—beautifully, boldly, and sometimes stubbornly—as a city where heritage still lives in the everyday.

And for that, I am grateful.

Text: Sundus Unsar Raja