THE ART AFICIONADO: SHAHZIA SIKANDER

Shahzia Sikander is one the most prolific artists in the art world. Currently living in the US, Shahzia believes her art connects her to the world – she is globally celebrated for an inventive approach towards art that takes classical Indo-Persian miniature painting as its point of departure, and inflects it with contemporary South Asian, American, Feminist and Muslim perspectives.

Shahzia Sikander will be the subject of a traveling retrospective titled Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities, 1987- 2003. The exhibition will open at The Morgan Library, New York in June 2021 followed by the RISD Museum, Rhode Island in November 2021, and MFA Houston, Texas in Spring 2022. On the occasion of these exhibitions, there will be a major new monograph published. Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities is an exhaustive examination of Sikander’s work from 1987 to 2003, charting her early development as an artist in Lahore and the United States, and foregrounding her critical role in bringing Indo-Persian painting into dialogue with contemporary art. Edited and with essays by Jan Howard and Sadia Abbas, it includes contributions by Gayatri Gopinath, Faisal Devji, Kishwar Rizvi, Vasif Kortun, Dennis Congdon, Bashir Ahmed, Rick Lowe and Julie Mehretu.

HELLO! spoke to the artist to talk about her inspirations, current work and future plans...

Photographer: Matin, NYC

Tell us a little bit about yourself. Have you always had a need to express yourself, to draw and paint?

Since I can remember, as a child, I would get transported into other worlds through books, especially poetry. There are fond memories of visiting Alif Laila Book Bus near our house in Main Market, full of different stories. Nature has a profound experience on a young child and for me it was how I started observing light, shapes, patterns, movement. As a preteen I was aware of my quiet and withdrawn nature and drawing allowed me to extract the unknown and the complex.

Do you come from a family of artists? How was your desire to pursue a career in the arts received by your family?

I was a studious child and also prone to day dreaming and it was clear that I had an aptitude towards creativity. All my CJM school report cards, sweetly saved by my father, from nursery to High School consistently say ‘responsible and good at Art’ – I was studying math and economics at Kinnaird College before I decided to go to NCA. It took some back and forth with parents, especially in those days, which is a long time ago, I mean the 1980s was a radically changing culture with the Zia’s decade and Hudood Ordinance hovering over youth. I applied for the domicile and the federal entrance test, came second in the art exam, got a scholarship to NCA and it was clear to them then how serious I was. I was inspired by women leaders like Asma Jehangir, Pakistan’s human rights activist. I was in search of a creative environment to reflect upon the mechanism of power and how women could be agents of change and that was fueling my direction.

Mid-Night Moment’ Gopi-Contagion, Times Square, NY.

You’re a graduate of one of the few art schools in Pakistan, the National College of Arts in Lahore. Do you feel like having received your initial education in the arts in Pakistan has shaped you as an artist?

Absolutely! My thesis ‘The Scroll’ 1989-90 at NCA was a game changer for contemporary miniature painting, receiving national attention. I was teaching at NCA in March of 1992, even before we officially had our postponed convocation.Teaching alongside the master Bashir Ahmed signaled to many students on the sideline that miniature painting could be readily embraced as a subject to specialize in. My work created a rupture at NCA bringing miniature painting into focus in 1990. I did not abandon that foundation and it still serves a role in my work and interest in opening up discourse around tradition and the avant-garde in various branches of global art history, South Asian art and feminist critique.

Mary-Am Fountain

What made you move to the United States to pursue an education in the arts? Why did you not go study art in Europe or even continue to do so in Pakistan?

I felt too restricted by the power dynamics of academia at NCA as a young artist and teacher. Most importantly the visual material and history I wanted to research was outside of Pakistan. Much of the regional paintings and objects were looted during the colonial period and that material resides in storages of institutions outside of the country. I was also restless and wanted to explore the world outside of my knowledge. In those days it was hard to get scholarship sitting in Pakistan. Initially, I wanted to study in Baroda with Ghulam and Nilima Sheikh but couldn’t get the Indian visa. Then I got into Slade and RCA in London but couldn’t get any financial aid. I ended up writing to many people including Pakistani Ambassador to US, Abida Hussain, to support young women artists. That eventually created an opportunity to travel on a standby ticket on PIA to exhibit at the Pakistani consulate in 1993. I was unable to sell a single work despite the fact that it was all under 50 dollars. In hindsight that was a blessing. I decided to call up art schools in the US. This was pre-internet days and calling up art schools to make appointments was not unusual. I had all my unsold small miniature paintings as a portfolio to show in person. I got accepted at many schools, including Maryland college of Arts, Boston Institute of Fine Arts, Art Institute Chicago. I chose Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) as the President of the school responded to my letter for financial assistance by letting me and another student stay in the basement apartment of the President’s house. I also researched in public libraries on funding available for international students and located an organization of women that paid for the tuition of graduate women. I also shared that information with the artist Ambreen Butt who also applied and got the same scholarship. There were many rejections along the way but I was able to work my way financially through school in the US, from babysitting, being a TA to the historian Mary Anne Staniszewski, recruiting future students interested in RISD, to even palm reading on Thayer street, near Brown University! I am now on the board of trustees at RISD and it gives me immense pride in shaping the direction of the institute, one of the most important art schools in the world.

Oil and Poppies

You’re most well-known for your interpretation of miniature painting, a very traditional form of art from our part of the world. Did you always want to master this traditional discipline or was your aim always to reimagine that art form? What is exactly ‘our part of the world’?

Miniature Painting is not restricted to Pakistan. My work is based on studying the arts pillaged during colonial histories. For me it is imperative to study the physical material and to research its provenance and for that I end up working in different parts of the world. A great book I’d recommend is the ‘Brutish Museum’ (not British) by Dan Hicks. The British Museum houses one of the world’s largest stolen properties and much of it is not on public display. I work with historians from across the world around archives and sociology of the arts. One important Pakistani historian is also Manan Ahmed based in New York, and his book ‘The Loss of Hindustan, The Invention of India’ is also an interesting parallel between our respective practices. The East India Company’s role in transforming trade and the world interests me and how digging into that history is very much digging into a contested history of colonialism. Trade, slavery, migration, colonial occupation – these are underlying currents, the root axes of modernity. How history is told, who gets to tell the story is about hierarchies of power and my interest in decolonizing the space of miniature painting and feminist critique is about re-imagining that history.

Who or what inspires your work the most? Is it a particular aesthetic, (apart from miniature painting obviously) a person or people or even an idea?

It is not just one thing. I am interested in the status of the migrant and cultural power, women and power, human and nature, in frameworks that restrict definitions to pure national and cultural histories and identities. Histories are not one dimensional nor societies static. Power in the time of the East India Company isn’t really all different than today. Our ecological condition is a mirror of social conditions: erosion of climate, of borders, rising waters, rising heat, displacement of bodies. These issues interest me deeply. I am constantly in conversation with thinkers engaged in these topics.

Flared

You live and work in the United States, does your work help keep you connected to Pakistan?

My work keeps me connected to the world, not just Pakistan. Visiting family and friends in Pakistan as well as Pakistani friends and family settled in Canada, Australia, England too keep me linked with the larger desi community. I am regularly working on projects in Munich, Germany. I have lived in Berlin and Seville. I have also lived in Laos and Somalia. My work draws upon the multiplicity of experience and is about broad topics that transcend definitive ideology, nationalism and geography. Engaging with Pakistani-American thinkers like Rafia Zakaria and Sadia Abbas also keeps me connected to the desi-feminist spirit. I am also part of the interdisciplinary platform Ideasandfuture.com and we are open for any Pakistani who’d like to submit an original art or text.

Why? Do you have a favourite artist from Pakistan in particular? How do you see Pakistani art evolving in general?

All artists in Pakistan are great, and art has been evolving for generations. We are also at a turning point when social media access is likely to allow a new generation of artists to move and lead in uncharted ways. Art will become increasingly interdisciplinary.

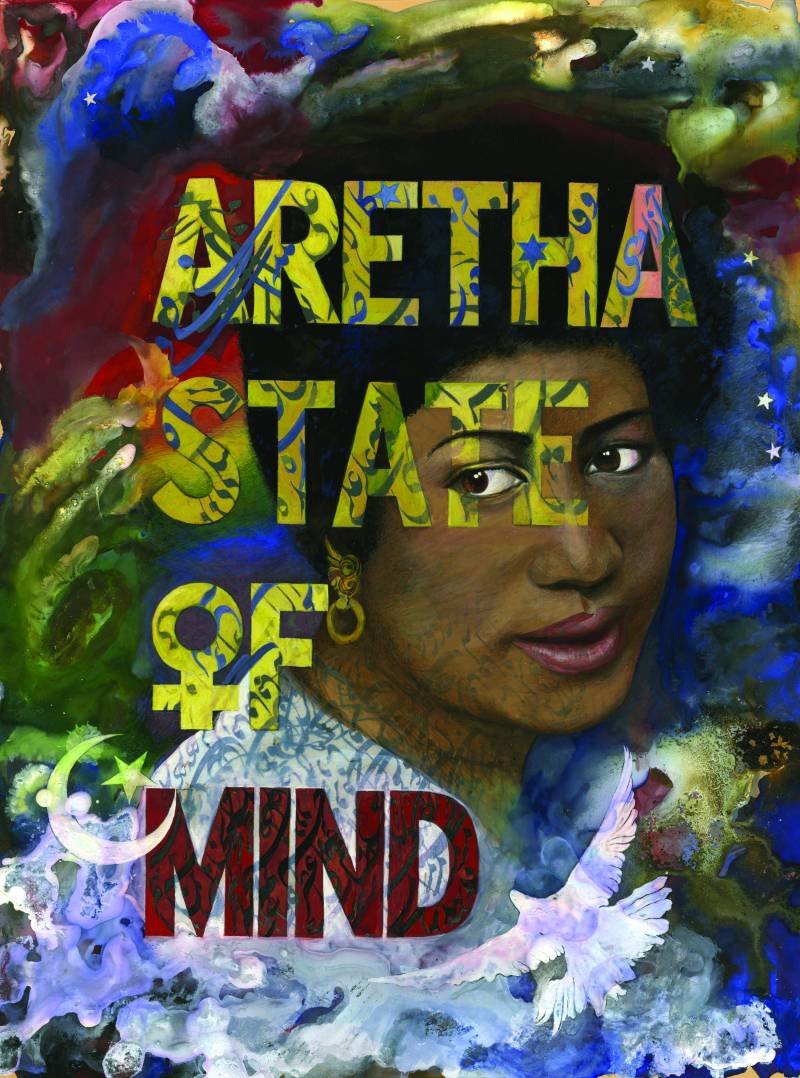

Aretha Sate of Mind

If one looks at the body of work that you’ve created over the years, we see you’ve evolved into a multimedia artist and you express yourself using a lot of different mediums. How and why did that come about?

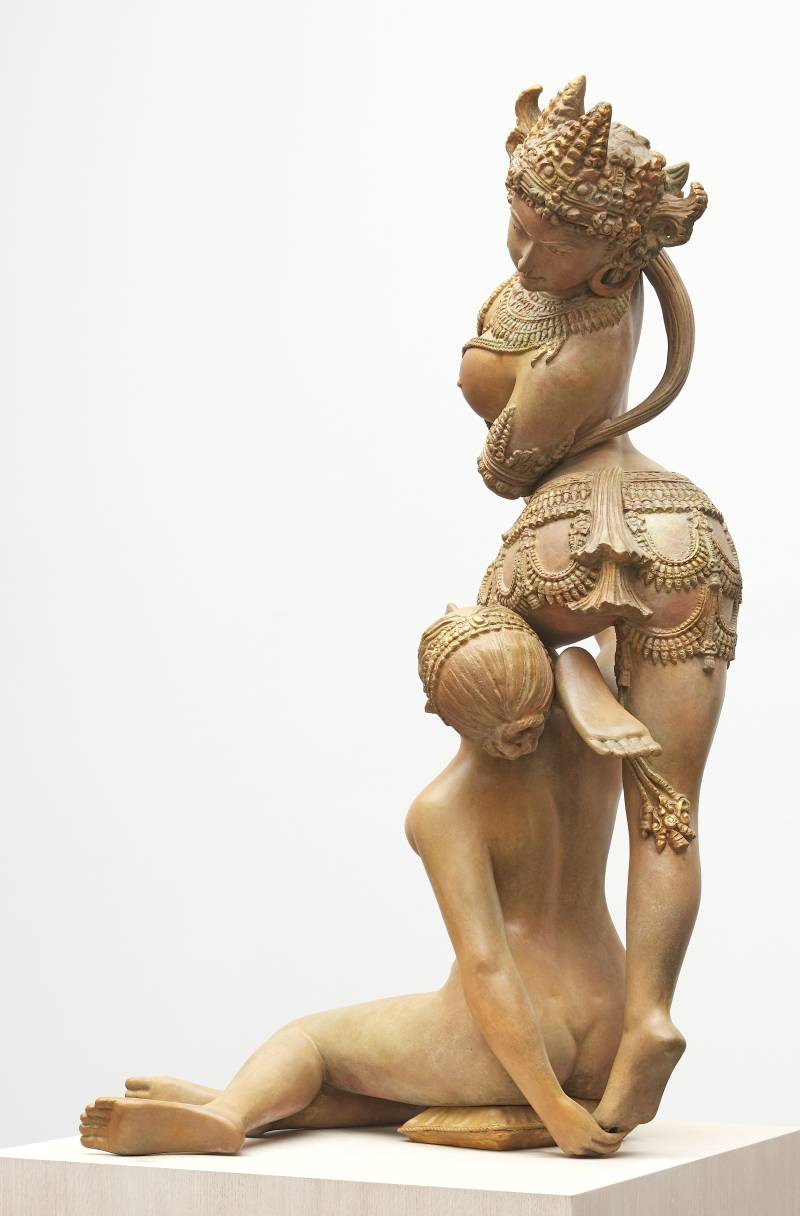

Critical thinking, creativity, and collaboration are the three tenets on which I have built my entire understanding of being an artist. How culture, society and economy intersect and how communities coalesce, plays a role in how art functions in overlapping spaces. Whether its painting, music, literature, theater, ceramics, sculpture, calligraphy, crafts, film, all art plays a role in how humans see each other and communicate. There are many stories and many points of views. Drawing is my thinking hat. I’m interested in transformative ideas and as ideas evolve so does the direction in my art. As Frantz Fanon says, ‘the real leap consists in introducing invention into existence’.

What do you do when you’re not creating something? Do you need to stop and unwind or working the ultimate form of relaxation?

I like walking, everywhere. It helps me clear my mind and connect with the surroundings. I read a lot. It expands my thinking and awareness, like meditation.

Promiscuous Intimacies

Finally, let’s end with something a little bit fanciful. If you could curate, the perfect exhibition (of any artists and their work from any time in history) what would that look like? Who would feature in it and which of their works?

This is an interesting question! I have many ideas, mostly around critical consciousness, to explore injustice by examining historical representations. An exhibition that culls out the unknown female miniature painters from the annals of time, especially during the 16th and 17th century. We hardly know anything about them. I would like to have Fahmida Riaz interview them. A live conversation between Ibn Arabi and Nusrat Fateh Ali khan would be riveting. I’d like to collaborate with Zubeida Agha and Sadequain. I would also love to curate a project that speaks to the subjectivity in science, between students of science and art in Pakistan and invite Qurratulain Hyder and Abdus Salam to lead the topic. Art is really about thinking outside of the box, about stretching our hearts and mind, connecting imagination and knowledge and about problem solving.

Arose

INTERVIEW: H! Pakistan

PHOTOS: COURTESY SHAHZIA SIKANDER